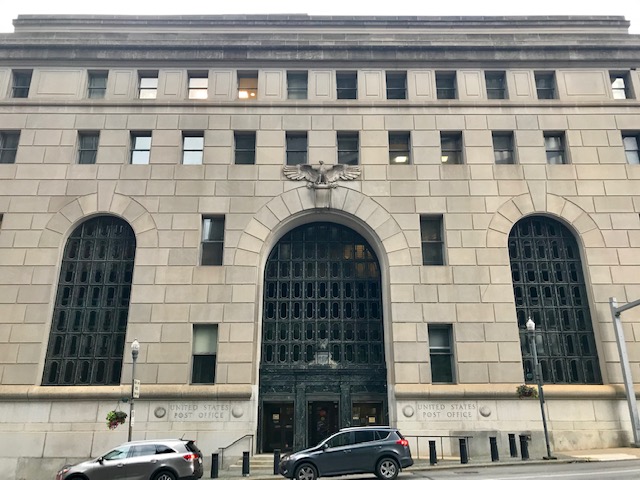

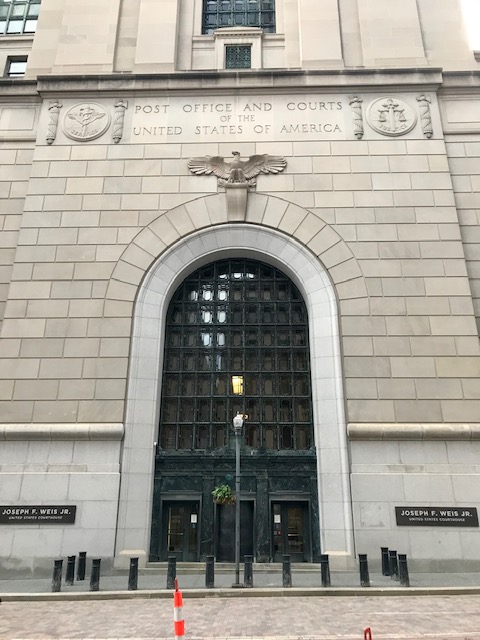

The United States Post Office & Courthouse (Weis Courthouse), located at 700 Grant Street, was constructed in 1934 to replace the five-story granite building at Fourth Ave. & Smithfield St. which was too small to handle demand almost as soon as it opened in 1891. The monumental Neoclassical masterpiece is one of the best examples of the style and houses two of the four WPA murals that exist within our city.

The US Post Office & Courthouse is significant because of its exquisite use of Neoclassical design, its association with a nationally-renowned architectural firm Trowbridge & Livingston, and that it is a prominent visual feature in downtown Pittsburgh.

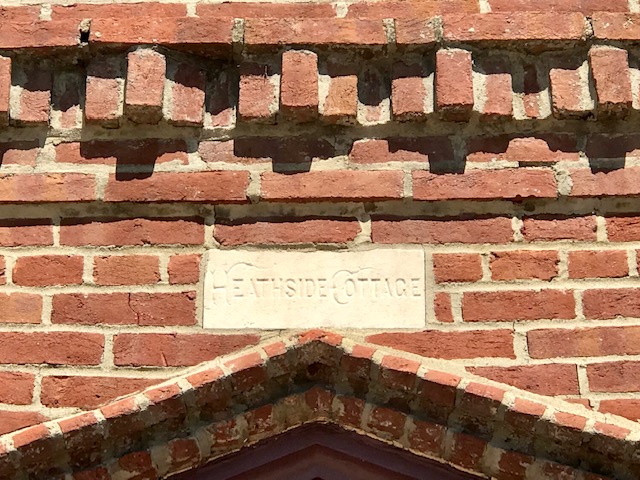

![Screenshot_2019-05-02 HABS PA,2-PITBU,33- (sheet 4 of 6) - Heathside Cottage, 416 Catoma Street, Pittsburgh, Allegheny Coun[...].png](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5544da4fe4b0528c14b3a224/1558059151105-5RLDAEESHQLZOUH8O2DC/Screenshot_2019-05-02+HABS+PA%2C2-PITBU%2C33-+%28sheet+4+of+6%29+-+Heathside+Cottage%2C+416+Catoma+Street%2C+Pittsburgh%2C+Allegheny+Coun%5B...%5D.png)